Extract data with a Java client

This guide will show you how to connect to a Deephaven instance with a Java client, and use it to extract data and tables.

While Deephaven Community Core provides a rich set of features directly through its Web IDE, it also excels at delivering the value of that analysis to other external systems.

We can easily imagine Deephaven providing market analysis data to an external trading engine, or analysed sensor data to a powerplant control system.

We will show you how to construct a simple system that: monitors weather data (sourced from NOAA), performs some analysis, provides the results to a Java application that controls what cities are monitored, and displays results, all with live ticking data.

Prerequisites

- Clone the Deephaven Community repository.

- Build and run Deephaven.

- Create a valid Google Geolocation API key.

The application

The application is broken up into three major parts:

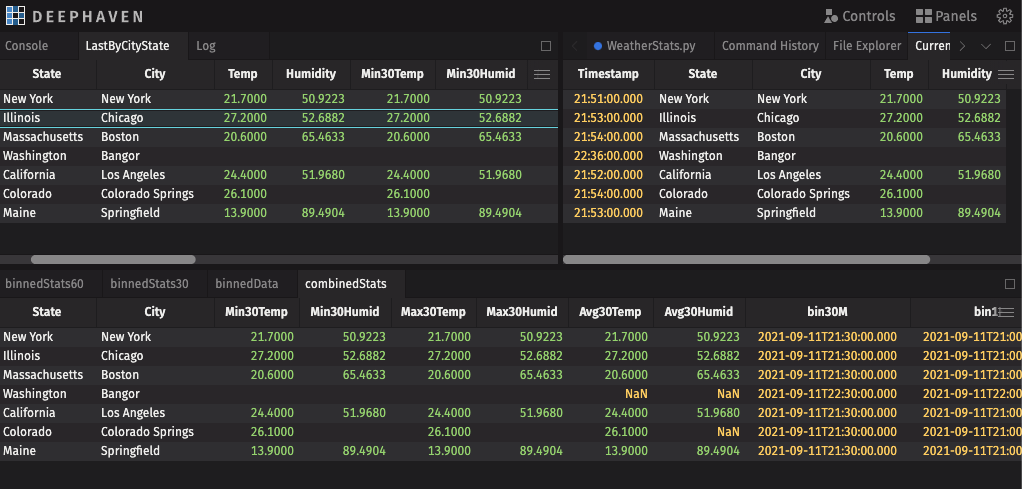

- The first part creates the Deephaven table where weather data will be recorded, and then creates several derived tables that will analyze the data to produce some simple statistics. Each of these tables will be visited in more detail in the following sections.

- The second part is a handful of simple Python methods that will extract position and weather data from the Google Geolocation API and NOAA's weather data API and record it. It also provides a method for the external java application to add more cities to be monitored.

- The final part is a very simple Java application that connects to the Deephaven worker and pulls the ticking results to be displayed. It also provides some simple functionality to add more cities to be monitored, demonstrating that complex Client/Server applications can be built directly with Deephaven.

Running the Python weather server

At this point, you should have a running Deephaven IDE. You first need to configure and run the Python Weather Server script. This is broken down into three major segments.

- Import the libraries needed into the worker.

Note

Note that the 'requests' library, which is used to do simple GET calls, is not part of the default Deephaven Python image, so it is imported directly into the running session. See How to install Python packages for more details.

- Create the DynamicTableWriter that will be used to ingest ticking data.

This simply creates a table with five columns to which the application will record weather measurements.

| Column | Type |

|---|---|

| Timestamp | DateTime |

| State | String |

| City | String |

| Temp | double |

| Humidity | double |

-

Perform some simple data analysis.

-

Create a data structure for collecting information on each location to use to fetch weather data.

Note

In the code below, be sure to insert your Google Geolocation API key into the

API_KEYvariable. -

Add the code that fetches weather data.

FetchWeatherData.py

The Python code above is compressed for brevity, but essentially contains four methods:

- A method to turn a Location name into a position using Google Geolocation.

- A method to discover the NOAA Weather API Endpoints for the position.

- A method to fetch the current weather observation for the position.

- A thread that fetches the current weather for all requested cities every 1 minute.

At this point, you have a completely functional Deephaven application that is ready to start providing data to another client.

The Java client

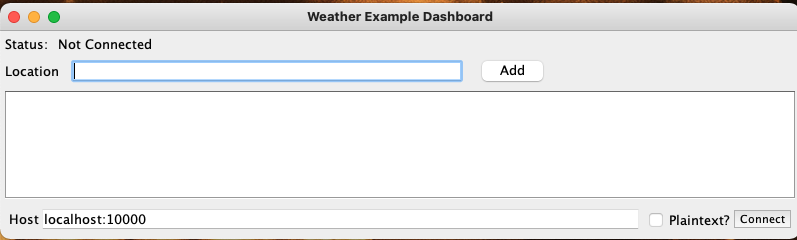

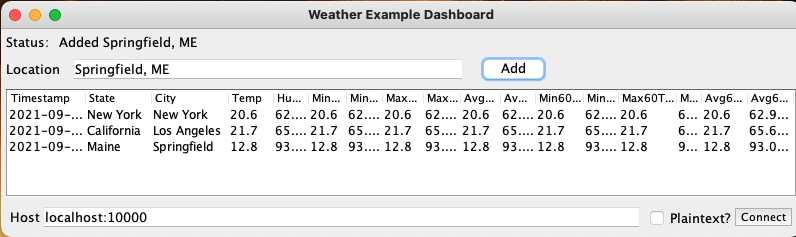

The final, and most interesting part of this example, is the Java client. It is an extremely simple Java Swing UI that has the ability to connect to the Deephaven worker and fetch the final LastByCityState statistics table. It also demonstrates the ability to communicate with the worker by requesting additional cities to be tracked.

The client code can be found in the repository in the java-client/weather-server-example directory. Build this and run the WeatherDash class to bring up the UI.

Enter the address of your Deephaven IDE and click Connect. Then type an address in the Location text box and click Add.

You will now see live weather data for the city you entered.

How it works

The Deephaven Java Client provides two major features to users:

- It provides a lightweight API that fetches Apache Arrow Flight data streams for users to work with. If you're familiar with Arrow Flight, and this is the format you want, then you can use this directly.

- It also provides the ability to transform the Arrow data stream directly into a local, ticking, Deephaven Table! Many users will want to use the power of Deephaven tables directly.

Note

The Java Client code makes extensive use of the Builder pattern to make object construction more expressive and natural.

The first part is to create a ManagedChannel. This is the root connection between your application and the Deephaven worker.

Once you have a channel to the worker, we need to create a FlightSession. This class layers the Deephaven logic on top of the raw channel to the worker.

Warning

The Deephaven Java-API is still an alpha library. In future versions, the method described below to convert the Arrow Flight Stream into a Deephaven table will be dramatically simplified.

This example has packaged this code into the class BarrageSupport to separate this complexity.

Now, we will create the BarrageSupport instance and fetch the LastByCityState from the worker.

Note

This is where the magic happens! In step 3, we defined a query-scope variable named LastByCityState. To reference in a remote client, we convert it into a Flight Ticket simply by prefixing s/. Any tables that are exposed in the query scope can be accessed as easily as that.

At this point, the variable statsTable is now a live, ticking, local instance of the table created in the Python script. This application simply displays the contents of that table directly, but a more sophisticated app could use this table data in any way it likes.

Bidirectional communication

One of the other exciting features of the Java client is the ability to communicate directly with the worker. This communication can be as sophisticated as creating even more specific derived tables using the same natural query language that is so powerful in the Deephaven Web IDE.

This example gives the user the ability to add cities to the set of monitored locations.

This simply sends a Python command to the server (beginWatch(place)) and checks for an error response. The server returns a Changes object, which allows the application to determine what has changed in the scope of the worker (for example, tables being created or variables being changed).

Warning

This example embeds a user string into a command. Be extremely careful to escape quotes and other special characters within the string to prevent script injection attacks.

Listening to Deephaven tables

The last piece of the puzzle is to process the data from the table. You can, of course, directly read the data from the table. You can also "listen" to the table, which allows the application to respond to ticking changes in the table.

Table subscription deep dive

As mentioned above, creating a subscribed, local Deephaven table will be easier in upcoming releases. However, below we discuss briefly what the example does.

First, the application needs to "export" a table from the server. This is done by requesting a TableHandle from the server, and then retrieving the Ticket object from it. The Ticket can be thought of simply as a unique identifier for a particular table stream.

Next, it must fetch the Schema of the Flight Stream. This tells the Deephaven libraries how to interpret the bytes from the Flight stream and convert them into Rows and Columns of a table. From this schema, this creates a TableDefinition and finally a BarrageTable, which is the core of the client side Deephaven table implementation.

Finally, we create a subscription to the server, which effectively tells the server what rows and columns the application requires, and starts the stream of data from the server.

With that final step, the Deephaven Table is subscribed, and will receive live updates from the server as data changes. Client code can then further listen to that table to handle changes as required.

Caution

When your app is done using tables that were fetched, be sure to call resultSub.close() to release any resources that are being held. Without this, the server believes the table is still active and will continue to consume memory and CPU time.